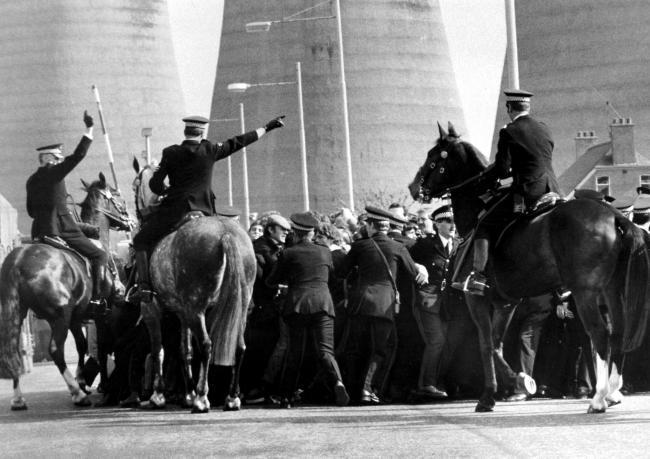

AN INDEPENDENT review into the policing of the miners strike in 1984-85 heard from Fifers who claimed they were arrested falsely and beaten by cops, of 'snatch squads' targeting union officials and kids as young as three in Valleyfield shouting 'F***** scabs' at strike-breakers.

It was told of men in army-style jackets and balaclavas trying to form a barricade in Oakley, "terrifying" violence at protests, vehicles being set on fire, soldiers masquerading as cops, miscarriages of justice and an official Fife police report admitting they had used "excessive force" on picket lines.

The inquiry, led by John Scott QC, gathered evidence from across the former coalfield areas of Scotland and heard that 200 miners were sacked – including some who were acquitted of any crime – and blacklisted, with more than 500 ending up with punitive fines and a criminal record for trying to save the coal industry.

More than 30 years on, there is still bitterness about the way they were treated and the role that 'Maggie's boot boys', as the force was tagged, played in the dispute.

The final report on the 'Impact on communities of the policing of the miners' strike 1984-85' was published recently and said: "In addition to the wider loss of trust and sense of legitimacy of the State, there have been powerful personal impacts of the strike.

"Some men reported being crushed by the combined loss of work, employability, income, family, self-respect and dignity.

"Some men suffered nervous breakdowns and some even committed suicide, such illness and death attributed by men and their family members to the events of 1984/85 and the lasting consequences of the strike."

It also said: "The impact of convictions went beyond the men affected, touching their families and communities, both in terms of the financial consequences of dismissal and unemployment, as well as confidence in the police, judiciary and the State."

A seismic event in recent British history, the year-long strike from March 6, 1984, to March 3, 1985, resulted from a dispute between the mining unions and the National Coal Board as pits across the country were earmarked for closure.

It led to violence between miners, pickets and the police, with allegations that Margaret Thatcher's Tory government was using the long arm of the law as a political tool to help smash the unions' power and close the coal industry down.

In Scotland, the number of striking miners was approximately 14,000 and, by the end of the dispute, approximately 1,400 had been arrested with more than 500 convicted.

Mr Scott's report said: "In part, the strike was different because of the lack of effort on the part of government to address the economic implications of pit closures in local communities, in particular by providing alternative employment opportunities for those who lost not only jobs but careers.

"This has exacerbated the damage to these communities."

The independent review was ordered finally in Scotland in 2018 and the inquiry held sessions where those who were impacted, including former miners and police officers, were encouraged to tell of their experiences.

Those memories, and the scars they left, still run deep with an acknowledgement that some of the former coalfield areas have never really recovered, with jobs taken away and communities destroyed, while men who hadn't been in trouble before or since still carry the stain of a criminal record.

That's set to be tackled, with justice minister Humza Yousaf announcing plans to introduce legislation that will offer them a pardon.

Ex-miner and former Dunfermline councillor, Bob Young, 77, told the Press last week that won't mean much and vowed to fight for compensation for the workers and families who lost jobs, pensions, relationships and even their lives.

The inquiry was told of individual strikers being picked out, as well as false arrests, lengthy spells of detainment on remand, physical abuse in custody by police officers, verbal threats and intimidation in the community by police officers, and highly-punitive sentencing, including fines of £350 to £400 for public order offences.

Miners who were arrested but not convicted – and even some who were acquitted – were sacked, which led to loss of income including pension contributions, subsequent financial hardship, loss of self-esteem, pressure on family and marital relationships and negative effects on physical and mental health.

The inquiry said they considered such dismissals were, in the circumstances, "disproportionate, excessive and unreasonable."

Many miners were blacklisted and found it very difficult to get another job, some said they never worked again, while others complained of a miscarriage of justice, with police officers they'd never seen before standing up in court to give evidence against them.

The only sacked miner in Britain to win his job back, Bob described the 'politicised' nature of the policing and said union officials were targeted deliberately for harassment and arrest.

Chair of the strike committee at the time and high up in the National Union of Mineworkers, he recalled how he had walked round the back of a police van at a protest and saw photos of himself and other high-ranking union members inside.

Arrested five times in total, he received a criminal conviction after disturbances outside Cartmore pit, Lochgelly.

Away from the demonstrations and picket lines, there was violence and threats against those who didn't strike, including smashing the windows of the houses of miners who had returned to work and a car and garage, that belonged to a miner who was working through the strike, being set on fire in Lochgelly.

The inquiry report includes source material from the time.

A Fife Constabulary debrief report from 1985 acknowledged there had been "excessive use of force" by police and that arrest reports for miners "were on occasions of fairly poor quality".

It also said there was little trouble in Oakley until two miners "decided to go back to work and break the solidarity of the village in its support for the strike".

The police report added: "This resulted in serious outbreaks of disorder, the worst being setting fire to an upturned van on Sligo Street and trying to form a barricade by a group of men dressed in army-style jackets and balaclava hoods with eye slits."

It said female pickets would turn up at Longannet every morning "to shout filthy phrases at the women going to work" in the offices there, while children as young as two or three in Oakley and Valleyfield would shout "f****** scabs" and "f****** scab polis".

The inquiry was told much of the violence was down to the increasing use within policing and mining of men from elsewhere, reinforcements and flying pickets.

Officers who came from mining families felt the pressure of being there and simply doing their job; many lived in mining communities, with one officer's wife repaying the kindness they were shown in Blairhall by helping out in the soup kitchen.

There were many acts of charity and compassion on both sides, with officers often putting money in collection tins for miners.

A number of miners did not blame individual officers, believing senior officers must carry the can for obeying the commands of the government, although political interference was denied by the chief constables who were in charge of areas with pits.

The forces also denied that soldiers were involved in the dispute, despite many telling the inquiry of individuals in ill-fitting police uniforms, of those not tall enough to be police officers or who didn't have numbers visible on their uniforms, as well as hearing second-hand of men seeing family members in police uniform who they knew to be soldiers.

Mr Scott's inquiry report said: "Regardless of suspicions, or even certainty on the part of some, of political interference, it is inconceivable that the police could simply have stood back entirely during the strike.

"The police had a duty to keep the peace and safeguard all members of the public, including miners, whether striking or working, as well as property."

It continued: "If our recommendation for pardons is accepted, it would be a positive approach by the Scottish Government to what it recognised as 'scars' from the strike.

"It would assist some by restoring some of what was lost, in particular the good name and respectability of honest working men engaged in trying to save their industry.

"It would address some of the 'mistakes' of the strike, many of which are the responsibility of the State, albeit not all through policing.

"As recognised by the police, the strike involved a 'most unusual atmosphere and conditions' and the men, women and families still affected by it as we have described are entitled to a 'most unusual' remedy."

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel